“Hey Octopus, what’s the best thing to play with your friends?” No one has ever asked me this, but don’t worry, I’ll answer it anyway; tabletop RPGs. Colloquially referred to by the ‘TTRPG’ abbreviation, these are games of collaborative storytelling that combine structured rulesets, often involving dice, with elements of make believe and ‘theater of the mind’ that sees players create their own characters to do random nonsense with. They meld these elements to let players make their own fun as they roll said dice in whatever adventurers that they end up creating together. This is at the expense of the eternally suffering ‘gamesmaster’, the person in charge of telling the story as it unfolds and presenting the obstacles the party faces. Such is the Sisyphean agony of the gamesmaster, tasked with endlessly attempting to coral players into their ‘planned storyline’ only for the high functioning adventuring sociopaths to keep asking ‘what’s over here instead?’ over and over again.

Here we see some new players learning how to play the game by asking the DM their first nonsense question; “What do you mean we can’t kill the entire town just because the gate guard wouldn’t give me his life savings? I rolled a persuasion check! This game sucks.” This is an important step towards becoming a player.

Everyone has heard, at least in passing, of the gold standard poster child of the genre, Dungeons and Dragons, and if you haven’t I’m honestly surprised you’ve found that deep of a rock to live under. The fantasy TTRPG, commonly considered ‘the first’, launched in 1974 bringing fantastical medieval roleplaying to the forefront of the genre; by the early 80’s, it was a cultural juggernaut. How was that game created, and what inspired it? Well, first I think we need a history lesson.

When I decided I wanted to cover TTRPG systems (it's still retro gaming technically!) I thought of how best to do it. Did I just want to jump into specific game systems first? Did I want to approach them as if I'm describing them to people who have never played one, or assume some basic context in the audience? That didn't take me long to figure out, as I am in fact going to cover specific game systems and do it as assuming the average reader has only a cursory level of context. My next obstacle was how to approach the first game I wanted to cover, being the only real option for the first review; the original first edition of Dungeons and Dragons. With that out of the way, I’m free to do whatever I want. There's a lot of history with it to summarize, and a lot of inspiration to cover. So I decided to split it up; I'm opening with this history article on the first baby steps of the TTRPG genre leading into the golden grandaddy, then I’ll do one dedicated to the system itself for my first specific game deep dive. After this, I’ll focus on specific game reviews but maybe I’ll revisit this history series if the mood strikes me; there’s always the golden years of the 80’s to cover, or the explosion of competition in the 90’s, the revival and renaissance of the early 2000’s.

With this usual rambling out of the way, let’s look at the first steps of the genre with the first inspirations that paved the way. The origins of tabletop roleplaying games are two-fold; tabletop wargames, and the proto roleplaying games. Wargames refers to a game system that simulates some form of military style battle between players; common examples include Risk and chess. It’s the combination of essentially a wargame rule set combined with elements of roleplaying and storytelling that is the TTRPG. Without the roleplaying aspect, you'd just be playing a board game; and without the ruleset aspect, you'd just be playing schoolyard make believe. Before we get into D&D, let’s go through the history of both those inspirations and see how they ended up coming together. Let’s start with the wargame, and to do that let’s go to the first place anyone would think to look; in the former Germanic state of Prussia in the early 1800’s.

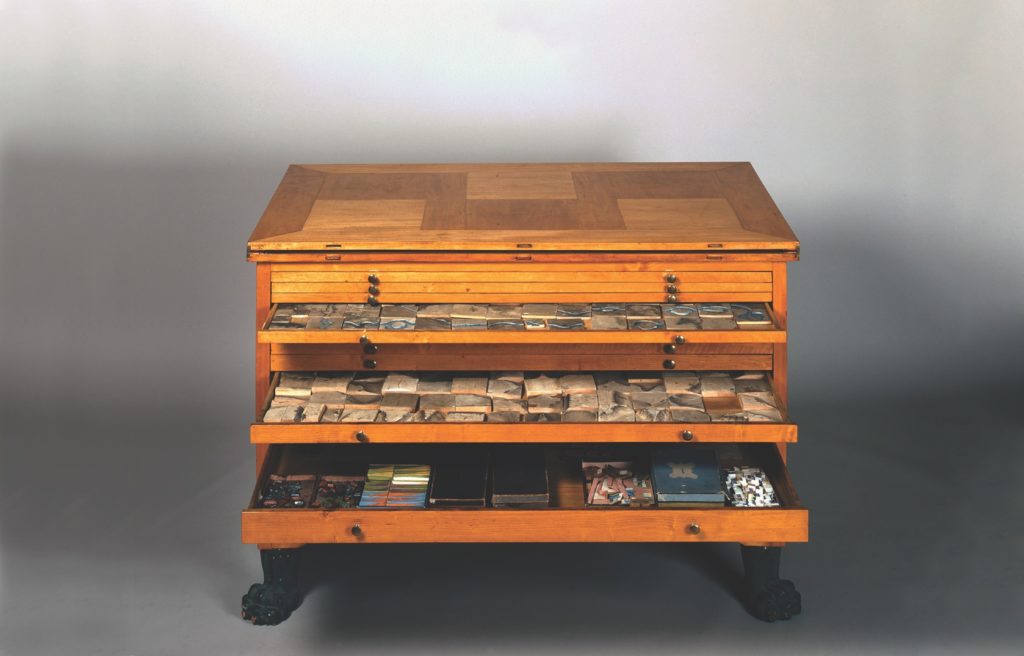

A version of the first kriegsspiel table, with the countertop being made of wood in this case. The cabinet was designed to store all the necessary pieces.

Players did not directly control their troops, represented by wooden blocks, on their turn; instead, they would dictate which actions they wished for troops to take and a neutral player known as the ‘umpire’ would then move the troops in a way he believed they would move when trying to follow said orders. This added a realistic human element into the game, as officers and generals could not also directly control their men in real war. Whenever the players' units engaged each other in combat, the umpire would be the one resolving the confrontation through rolling dice to determine the outcome, and calculating the casualties taken by both sides. The umpire was even called upon explicitly to fill in gaps the written rules of the game didn’t cover, as the umpire position was reserved for experienced officers and lieutenants who had actually seen combat. This experience was to let them realistically judge what would happen in circumstances that the games rules hadn’t covered.

Kriegsspiel is notable for a few reasons. It’s the first game to feature the role of a ‘gamesmaster’, here called an umpire. The name’s different, but the role is the same; a largely neutral third party. It’s also the first game to have a more ‘simulation’ approach to its rules. Chess and checkers both predate kriegsspiel by quite a many centuries, but both those games have rules that are in place just for the fact that it’s a game, independent of a sense of reality to it. Consider it this way; in chess, your horse-riding knight moves only in a four square L-shape, and your footsoldier pawns can move only forward, sometimes diagonally. It’s this way because it just is; it’s a contrivance done purely for the purpose of balance in the game. In kriegsspiel, the rules are attempting a sense of realism. Your troops can move in any direction you want and aren’t restricted by contrivances, just like in real life. It’s also one of the first games to incorporate dice rolling as a major part of the gameplay to introduce an element of unpredictability, an integral part of the TTRPG formula.

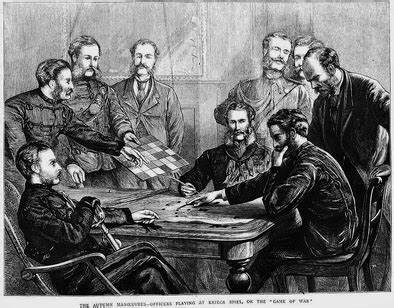

Only distinguished military men played Kriegsspiel- just look at the facial hair.

Kriegsspiel became known outside of Germany after the 1870 victory of Prussia over the French army during the Franco-Prussian War. The Prussian victory was attributed almost entirely to the wargame, as the Prussian army was outnumbered and had no clear advantage in terms of supplies and weapons over the French; the only thing they had was kreigsspiel being used as a training tool. This drew a lot of international attention to the game. It took only 10 years for the game to reach into the United States, with a version called Strategos, the American Wargame developed by Charles H.L Totten in 1880. Strategos was very similar to kriegsspiel, but had more of a focus on teaching inexperienced players; it came with ‘beginner’ scenarios that were intended to be worked through sequentially, slowly teaching players the game as they played. By 1873, a group of students and faculty at Harvard had started the University Kreigsspiel Club, which was the first observable time that the game was available for and played by civilians.

The genre of ‘wargames’ would evolve from this point as the decades went on, ultimately merging with the burgeoning miniature gaming movement of the 50’s; miniatures in this context referring to players making their own custom game pieces styled after different eras of military battles. Rulesets were designed and told by word of mouth or in independent hobbyist magazines, and games were held across both universities and kitchen tables with different sized miniatures. In this way, miniature wargaming could be considered one of the first ‘open source’ games; rules were designed and then essentially given away to players, who then ran it using their own pieces, or would modify the rules for their own fun. The game's themselves were still historically grounded, and often were based on real historical battles; they were ‘what if’ scenarios, seeing players attempt to change history through their tactical skill. Common settings included the naval battles of the colonial British era, Napoleon's attempted conquest of Europe, and the battle of Gettysburg from the American civil war. The games slowly crawled through every era of military battles, and eventually the first medieval era games began to appear around the mid 60’s. Siege of Bodenburg was a popular one, notable in that it was the first early work of a game designer who would go on afterwards to make a very important wargame in the history of tabletop roleplaying games (we’re still getting there); 1971’s Chainmail.

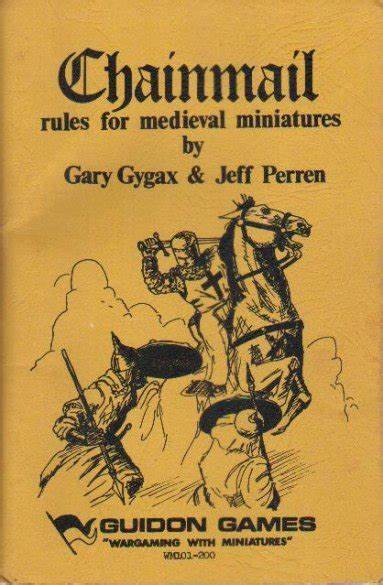

Indie publishing at its finest.

Normally, wargames up until now were designed with one particular idea in mind; armies fighting on a big map, with each individual unit representing a particular number of soldiers. Chainmail introduced optional rules for instead having smaller scale battles between individual units, referrered to as ‘heroes’, with each figurine being only one character. This was an important step for the genre, moving towards the small party combat dynamics of the TTRPG.

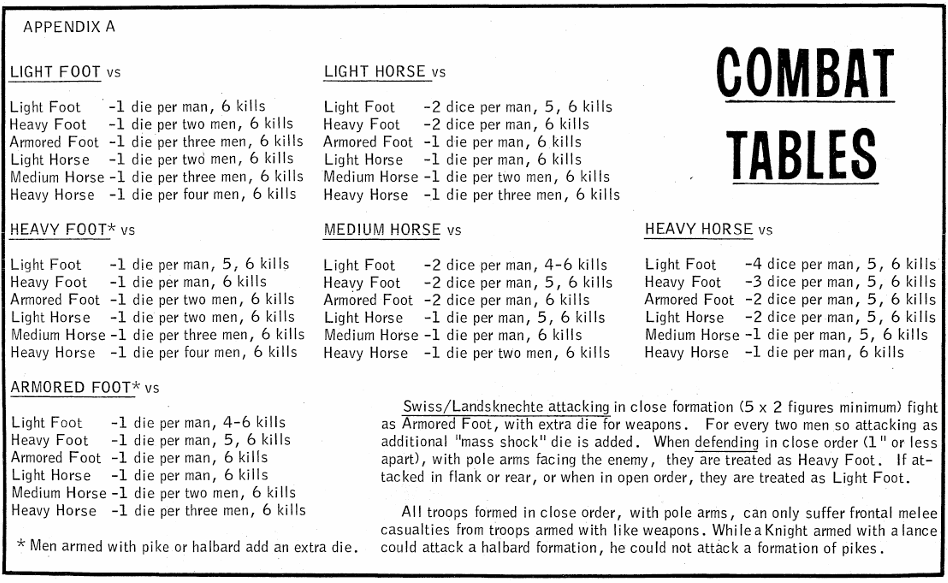

The combat rules were typical of wargames of the time, still following the same basic principles laid out over a century before in kriegsspiel. Combat was resolved by rolling six sided dice to determine the results, based on which units were fighting. Light footmen, the weakest individual unit for example, rolled only one die for every four footmen attacking against heavy cavalry, the strongest individual unit. When it came time for the heavy cavalry to hit back, they rolled four dice per attacking cavalry resulting in a better chance of more casualties on the poor lowly foot soldiers.

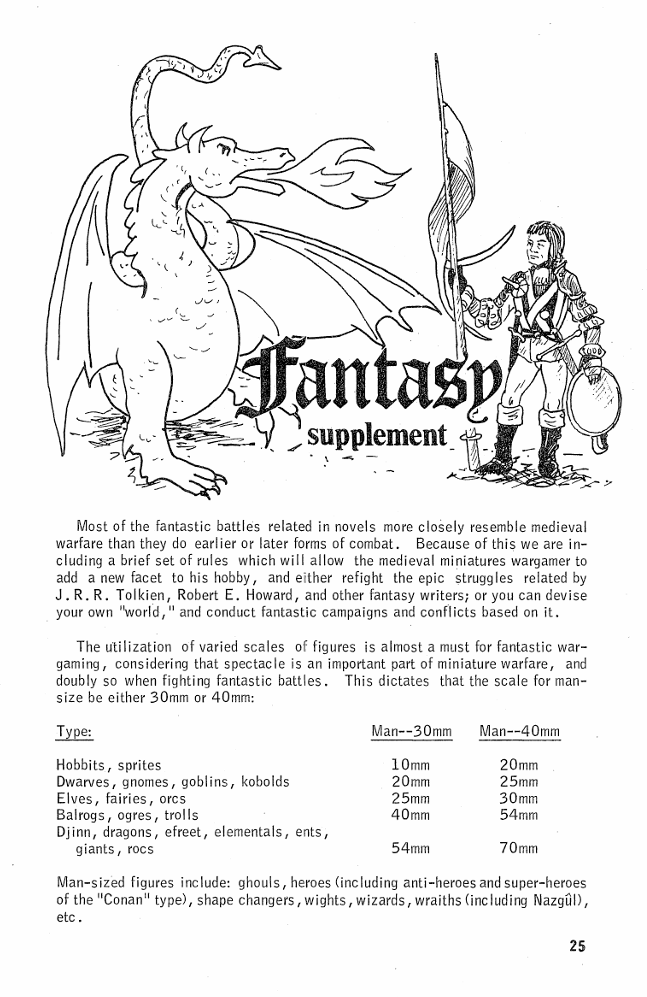

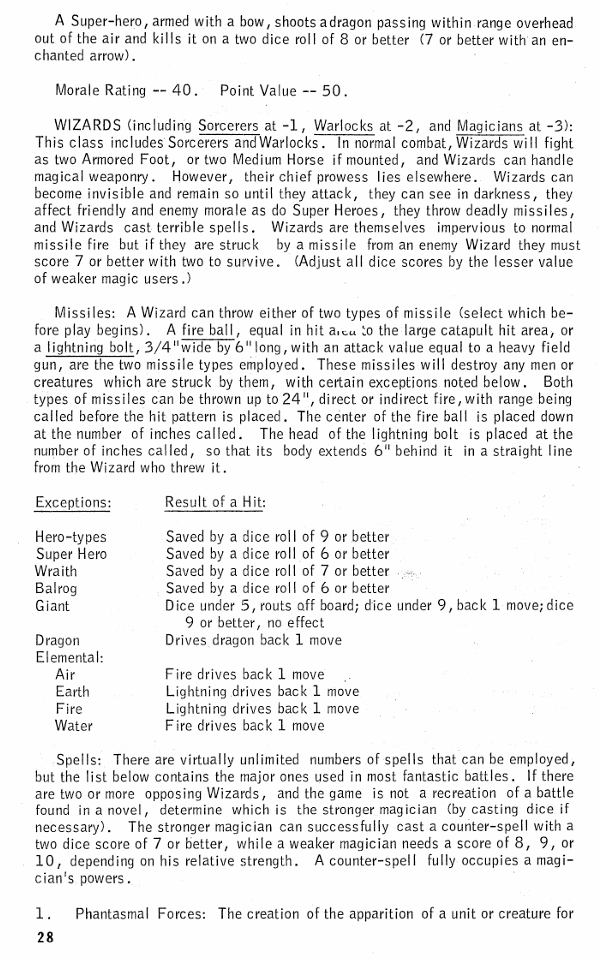

Chainmail also was another first; it was the first game to feature rules for playing with fantasy elements. The first edition launched with a 14-page section describing how to add in such things as trolls, elves, and spellcasting wizards into the wargame, giving rules and tables on how good dwarves are at hitting things and how many casualties are removed when a unit gets hit by a magical lightning bolt.

Whoever this mysterious game designer was (don’t look at the names on the cover in the last picture, let me have my dramatic name drop in the next paragraph), he definitely had an iconic writing style.

While there were rules you could follow for how many units each player could have, part of the appeal of Chainmail was allowing players to base their games off of novels or famous battles, letting them decide what each side could have. This free-form idea features into the magical wizard rules as well; note this sentence in the ‘Spells’ paragraph: “If there are two or more opposing Wizards, and the game is not a recreation of a battle found in a novel, determine which is the stronger magician.” The implication being the novel you’re recreating would tell you who’s the stronger wizard. It’s a good example of the vibe that early tabletop games had, of letting players' imagination fill in the blanks of the more vague rules.

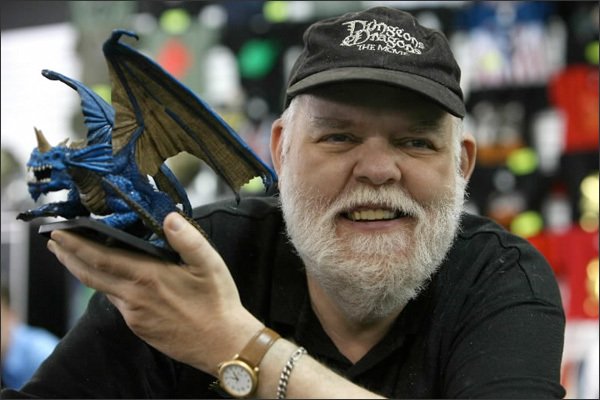

This mysterious designer's name? Gary Gygax. For those who don’t know, Gygax is considered the father of the TTRPG genre being one half of the creators of a little game called Dungeons and Dragons. See, we’re getting there. The other developer? We’ll find out. Before we do, let’s go down another historical avenue; where the ‘roleplaying’ elements came from.

Braunstein was a 1969 attempt from Minnesota physics student David Wesley to combine the elements of wargames, which he loved and developed previously as a member of the hobbyist group Midwest Military Simulation Association, and elements of a collaborative role-playing game such as a parlour game. He combined these by creating a fictional German town, the titular Braunstein, and designed it to be a game of Strategos played through players taking on the role of various town characters all set in his favourite time setting of the Napoleonic years.

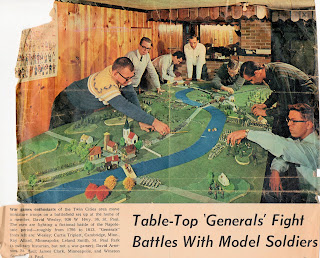

Here we see one of the first Braunstein’s being played. The man on the left leaning over the table is David Wesley. Who could that man be in the back in the green sweater? I’m sure he isn’t an important part of TTRPG history himself or anything, and one we’re building towards.

Two of these players were playing the role of military generals in charge of moving their troops around the town with specific objectives in mind; this was a revolutionary move. Instead of simply moving their pieces around a map and feigning combat like in kriegsspiel, these two players were actively playing the character of two generals instead. Actions were to be done by them taking Wesley into a private room, and announcing what their characters were doing rather than just simply rolling some dice and moving some army men around on a map; they were roleplaying as characters, instead of simply playing a wargame. When more players than intended showed up, Wesley assigned them roles of normal townspeople independent of the wargame with their own objectives; there was the town baker, the mayor, and some revolutionary university students among others. The result? Pure roleplaying chaos.

Players got really into their characters, and started going off making secret plans in corners of the room without informing Wesley. They started conversing in character to one another, describing what areas of town they liked to walk around in and talking about how their businesses were doing. It all came to a head when one player challenged another to a duel, and in lieu of actually having a duel take place, Wesley quickly improvised some rules on how these characters would fight, ending in one player’s character being stabbed dead. The players all absolutely loved it, and begged Wesley to have another. The irony? David Wesley allegedly hated it, and thought it was a complete failure. He was approaching it as a hardcore wargamer, the genre he loved so much that he was a member of the ROTC program in his university; he laid something out for the players, and he couldn’t understand why and how they were deviating from the plan. Why didn’t they want to move around their 16 divisions of artillery men? Why did the baker care about the banker? Because, as Wesley didn’t quite realize at the time, he had evolved his experiment past a wargame into something else; the first true tabletop roleplaying game. He combined the simulation style rules of a wargame with the addition of players collaborating on telling a story through the personification of a character in the game, and in doing so became the first true eternally suffering gamesmaster.

David Wesley running a Braunstein in 2022 at Garycon in Lake Geneva. He’s still going at it.

Dave Arneson, gaming legend. RIP, king. Oh, and he was the guy in the green sweater playing Braunstein.

He found the fairly sparse rules in Chainmail to not be to his liking, and so devised additions and expansions to it to create his own thing; this prototype ruleset was the creation of many contemporary TTRPG concepts, being the first instances of ‘character classes’, ‘armour class’ as the difficulty to hit a character in combat, and experience points and character levels. Eventually in November of 1972, he journeyed to Lake Geneva to try and pitch Blackmoor alongside another game creator to a representative of independent game company Guidon Games, publishers of various wargames and Chainmail itself; that representative was Gary Gygax.

We’re finally here, at this incredibly formative meeting in the history of TTRPGs; the merging of small scale combat rules of Chainmail, and the roleplaying focus of Arneson’s Blackmoor. The result? After Arneson ran Gygax and a few friends through a game of Blackmoor, they began a long distance collaboration that resulted in the game known as Dungeons and Dragons, and them forming the company Tactical Studies Rules (TSR) to self publish it. They took ideas and elements from the numerous previous games they had worked on and designed and combined them into the historic roleplaying experience of the game’s first edition.

In the next tabletop article, we’re going to do the first system review of the 1974 first edition of Dungeons and Dragons. This may come as a surprise, but I've never played first edition; I've played every other version through the preceding decades, but never the first. I know all about it of course, but have no experience actually sitting down at a table and playing it. So who knows; maybe we’ll both learn something new.

Until next time.

Here we see some new players learning how to play the game by asking the DM their first nonsense question; “What do you mean we can’t kill the entire town just because the gate guard wouldn’t give me his life savings? I rolled a persuasion check! This game sucks.” This is an important step towards becoming a player.

Everyone has heard, at least in passing, of the gold standard poster child of the genre, Dungeons and Dragons, and if you haven’t I’m honestly surprised you’ve found that deep of a rock to live under. The fantasy TTRPG, commonly considered ‘the first’, launched in 1974 bringing fantastical medieval roleplaying to the forefront of the genre; by the early 80’s, it was a cultural juggernaut. How was that game created, and what inspired it? Well, first I think we need a history lesson.

When I decided I wanted to cover TTRPG systems (it's still retro gaming technically!) I thought of how best to do it. Did I just want to jump into specific game systems first? Did I want to approach them as if I'm describing them to people who have never played one, or assume some basic context in the audience? That didn't take me long to figure out, as I am in fact going to cover specific game systems and do it as assuming the average reader has only a cursory level of context. My next obstacle was how to approach the first game I wanted to cover, being the only real option for the first review; the original first edition of Dungeons and Dragons. With that out of the way, I’m free to do whatever I want. There's a lot of history with it to summarize, and a lot of inspiration to cover. So I decided to split it up; I'm opening with this history article on the first baby steps of the TTRPG genre leading into the golden grandaddy, then I’ll do one dedicated to the system itself for my first specific game deep dive. After this, I’ll focus on specific game reviews but maybe I’ll revisit this history series if the mood strikes me; there’s always the golden years of the 80’s to cover, or the explosion of competition in the 90’s, the revival and renaissance of the early 2000’s.

With this usual rambling out of the way, let’s look at the first steps of the genre with the first inspirations that paved the way. The origins of tabletop roleplaying games are two-fold; tabletop wargames, and the proto roleplaying games. Wargames refers to a game system that simulates some form of military style battle between players; common examples include Risk and chess. It’s the combination of essentially a wargame rule set combined with elements of roleplaying and storytelling that is the TTRPG. Without the roleplaying aspect, you'd just be playing a board game; and without the ruleset aspect, you'd just be playing schoolyard make believe. Before we get into D&D, let’s go through the history of both those inspirations and see how they ended up coming together. Let’s start with the wargame, and to do that let’s go to the first place anyone would think to look; in the former Germanic state of Prussia in the early 1800’s.

Military Training Tools; Kriegsspiel

Kriegsspiel (loosely translated: wargame) was a Prussian military wargame played by officers to teach them battlefield tactics, with it being officially recognized by the Prussian army in 1824 and becoming commonly played in the military by 1860. Designed by Georg Heinrich Rudolf Johann von Reisswitz continuing from groundwork laid by his father, George Leopold von Reisswitz, the game was one of the first original games such as this to be produced and commercially sold, and the only one I know of that was officially used as a military training tool. It was played on a realistic map, complete with the same scale of topographic maps used by the military. The earlier version partly designed by George Leopold von Reisswitz was played on a custom cabinet using ceramic tiles with drawn on terrain as the playing field, but didn’t catch on due to the price of the unit and manufacturing issues.A version of the first kriegsspiel table, with the countertop being made of wood in this case. The cabinet was designed to store all the necessary pieces.

Players did not directly control their troops, represented by wooden blocks, on their turn; instead, they would dictate which actions they wished for troops to take and a neutral player known as the ‘umpire’ would then move the troops in a way he believed they would move when trying to follow said orders. This added a realistic human element into the game, as officers and generals could not also directly control their men in real war. Whenever the players' units engaged each other in combat, the umpire would be the one resolving the confrontation through rolling dice to determine the outcome, and calculating the casualties taken by both sides. The umpire was even called upon explicitly to fill in gaps the written rules of the game didn’t cover, as the umpire position was reserved for experienced officers and lieutenants who had actually seen combat. This experience was to let them realistically judge what would happen in circumstances that the games rules hadn’t covered.

Kriegsspiel is notable for a few reasons. It’s the first game to feature the role of a ‘gamesmaster’, here called an umpire. The name’s different, but the role is the same; a largely neutral third party. It’s also the first game to have a more ‘simulation’ approach to its rules. Chess and checkers both predate kriegsspiel by quite a many centuries, but both those games have rules that are in place just for the fact that it’s a game, independent of a sense of reality to it. Consider it this way; in chess, your horse-riding knight moves only in a four square L-shape, and your footsoldier pawns can move only forward, sometimes diagonally. It’s this way because it just is; it’s a contrivance done purely for the purpose of balance in the game. In kriegsspiel, the rules are attempting a sense of realism. Your troops can move in any direction you want and aren’t restricted by contrivances, just like in real life. It’s also one of the first games to incorporate dice rolling as a major part of the gameplay to introduce an element of unpredictability, an integral part of the TTRPG formula.

Only distinguished military men played Kriegsspiel- just look at the facial hair.

Kriegsspiel became known outside of Germany after the 1870 victory of Prussia over the French army during the Franco-Prussian War. The Prussian victory was attributed almost entirely to the wargame, as the Prussian army was outnumbered and had no clear advantage in terms of supplies and weapons over the French; the only thing they had was kreigsspiel being used as a training tool. This drew a lot of international attention to the game. It took only 10 years for the game to reach into the United States, with a version called Strategos, the American Wargame developed by Charles H.L Totten in 1880. Strategos was very similar to kriegsspiel, but had more of a focus on teaching inexperienced players; it came with ‘beginner’ scenarios that were intended to be worked through sequentially, slowly teaching players the game as they played. By 1873, a group of students and faculty at Harvard had started the University Kreigsspiel Club, which was the first observable time that the game was available for and played by civilians.

The genre of ‘wargames’ would evolve from this point as the decades went on, ultimately merging with the burgeoning miniature gaming movement of the 50’s; miniatures in this context referring to players making their own custom game pieces styled after different eras of military battles. Rulesets were designed and told by word of mouth or in independent hobbyist magazines, and games were held across both universities and kitchen tables with different sized miniatures. In this way, miniature wargaming could be considered one of the first ‘open source’ games; rules were designed and then essentially given away to players, who then ran it using their own pieces, or would modify the rules for their own fun. The game's themselves were still historically grounded, and often were based on real historical battles; they were ‘what if’ scenarios, seeing players attempt to change history through their tactical skill. Common settings included the naval battles of the colonial British era, Napoleon's attempted conquest of Europe, and the battle of Gettysburg from the American civil war. The games slowly crawled through every era of military battles, and eventually the first medieval era games began to appear around the mid 60’s. Siege of Bodenburg was a popular one, notable in that it was the first early work of a game designer who would go on afterwards to make a very important wargame in the history of tabletop roleplaying games (we’re still getting there); 1971’s Chainmail.

Mass Fighting in Chainmail

Chainmail was a miniature wargame notable for a few different reasons. It came at just the right time early in the medieval wargame subgenre to catch on and popularize it, and was one of the first games to include rules on multiple scales of play.Indie publishing at its finest.

Normally, wargames up until now were designed with one particular idea in mind; armies fighting on a big map, with each individual unit representing a particular number of soldiers. Chainmail introduced optional rules for instead having smaller scale battles between individual units, referrered to as ‘heroes’, with each figurine being only one character. This was an important step for the genre, moving towards the small party combat dynamics of the TTRPG.

The combat rules were typical of wargames of the time, still following the same basic principles laid out over a century before in kriegsspiel. Combat was resolved by rolling six sided dice to determine the results, based on which units were fighting. Light footmen, the weakest individual unit for example, rolled only one die for every four footmen attacking against heavy cavalry, the strongest individual unit. When it came time for the heavy cavalry to hit back, they rolled four dice per attacking cavalry resulting in a better chance of more casualties on the poor lowly foot soldiers.

Chainmail also was another first; it was the first game to feature rules for playing with fantasy elements. The first edition launched with a 14-page section describing how to add in such things as trolls, elves, and spellcasting wizards into the wargame, giving rules and tables on how good dwarves are at hitting things and how many casualties are removed when a unit gets hit by a magical lightning bolt.

Whoever this mysterious game designer was (don’t look at the names on the cover in the last picture, let me have my dramatic name drop in the next paragraph), he definitely had an iconic writing style.

While there were rules you could follow for how many units each player could have, part of the appeal of Chainmail was allowing players to base their games off of novels or famous battles, letting them decide what each side could have. This free-form idea features into the magical wizard rules as well; note this sentence in the ‘Spells’ paragraph: “If there are two or more opposing Wizards, and the game is not a recreation of a battle found in a novel, determine which is the stronger magician.” The implication being the novel you’re recreating would tell you who’s the stronger wizard. It’s a good example of the vibe that early tabletop games had, of letting players' imagination fill in the blanks of the more vague rules.

This mysterious designer's name? Gary Gygax. For those who don’t know, Gygax is considered the father of the TTRPG genre being one half of the creators of a little game called Dungeons and Dragons. See, we’re getting there. The other developer? We’ll find out. Before we do, let’s go down another historical avenue; where the ‘roleplaying’ elements came from.

The Early Roleplaying Games, and Pulling a Braunstein

Roleplaying refers to the act of players taking on the actions of a fictional character, embodying them and ‘making believe’ so to speak. Obviously, this concept is as old as our race itself, coming from ancient storytelling and eventually stage plays, television and movies. In the context of the inspirations of TTRPGs, however, the concept of roleplaying can be narrowed down to a few specific things. The first is what were known as the boxed ‘parlour games’ of the early 1900s. Inspired by the party games of the Victorian era, these games were designed to be played in parties and social gatherings, and were the first real examples of collaborative storytelling. A popular one was 1937’s Jury Box by the famous Parker Brothers, which I’m bringing up for more reasons than the fact it was actually manufactured in Canada as most Parker Brothers games at the time were. The game saw gathered participants act as members of a jury for six crimes included in the box; the goal was to decide if the accused was innocent or guilty, acting as a real jury; once again, one player was assigned the role of ‘judge’ or ‘gamesmaster’, here framed as the district attorney. From these games, came the most monumental influence of all; a little experiment called Braunstein.Braunstein was a 1969 attempt from Minnesota physics student David Wesley to combine the elements of wargames, which he loved and developed previously as a member of the hobbyist group Midwest Military Simulation Association, and elements of a collaborative role-playing game such as a parlour game. He combined these by creating a fictional German town, the titular Braunstein, and designed it to be a game of Strategos played through players taking on the role of various town characters all set in his favourite time setting of the Napoleonic years.

Here we see one of the first Braunstein’s being played. The man on the left leaning over the table is David Wesley. Who could that man be in the back in the green sweater? I’m sure he isn’t an important part of TTRPG history himself or anything, and one we’re building towards.

Two of these players were playing the role of military generals in charge of moving their troops around the town with specific objectives in mind; this was a revolutionary move. Instead of simply moving their pieces around a map and feigning combat like in kriegsspiel, these two players were actively playing the character of two generals instead. Actions were to be done by them taking Wesley into a private room, and announcing what their characters were doing rather than just simply rolling some dice and moving some army men around on a map; they were roleplaying as characters, instead of simply playing a wargame. When more players than intended showed up, Wesley assigned them roles of normal townspeople independent of the wargame with their own objectives; there was the town baker, the mayor, and some revolutionary university students among others. The result? Pure roleplaying chaos.

Players got really into their characters, and started going off making secret plans in corners of the room without informing Wesley. They started conversing in character to one another, describing what areas of town they liked to walk around in and talking about how their businesses were doing. It all came to a head when one player challenged another to a duel, and in lieu of actually having a duel take place, Wesley quickly improvised some rules on how these characters would fight, ending in one player’s character being stabbed dead. The players all absolutely loved it, and begged Wesley to have another. The irony? David Wesley allegedly hated it, and thought it was a complete failure. He was approaching it as a hardcore wargamer, the genre he loved so much that he was a member of the ROTC program in his university; he laid something out for the players, and he couldn’t understand why and how they were deviating from the plan. Why didn’t they want to move around their 16 divisions of artillery men? Why did the baker care about the banker? Because, as Wesley didn’t quite realize at the time, he had evolved his experiment past a wargame into something else; the first true tabletop roleplaying game. He combined the simulation style rules of a wargame with the addition of players collaborating on telling a story through the personification of a character in the game, and in doing so became the first true eternally suffering gamesmaster.

David Wesley running a Braunstein in 2022 at Garycon in Lake Geneva. He’s still going at it.

The Historic Meeting of the Nerds, and the Birth of Dungeons and Dragons

‘The Braunstein’, as it became known, was hugely influential in the local area and saw friends of Wesley running it after he got shipped off to active military officer duty. The most influential spin-off of ‘a Braunstein’ came from another fellow MMSA member, Dave Arneson. In 1971 he devised a version that he called Blackmoor, seeing the concept being transported to a magical fantasy realm. The game saw one major change; it was no longer a wargame in the traditional scale with players moving around armies on a large scale map. Instead, Arneson had his players combat monsters such as orcs and vampires in the dungeons of Castle Blackmoor (which was represented with a toy castle kit of the famous Branzoll Castle in Italy). The ruleset he used for these combats? The only game out there with rules for fantasy creatures of course, Chainmail.Dave Arneson, gaming legend. RIP, king. Oh, and he was the guy in the green sweater playing Braunstein.

He found the fairly sparse rules in Chainmail to not be to his liking, and so devised additions and expansions to it to create his own thing; this prototype ruleset was the creation of many contemporary TTRPG concepts, being the first instances of ‘character classes’, ‘armour class’ as the difficulty to hit a character in combat, and experience points and character levels. Eventually in November of 1972, he journeyed to Lake Geneva to try and pitch Blackmoor alongside another game creator to a representative of independent game company Guidon Games, publishers of various wargames and Chainmail itself; that representative was Gary Gygax.

We’re finally here, at this incredibly formative meeting in the history of TTRPGs; the merging of small scale combat rules of Chainmail, and the roleplaying focus of Arneson’s Blackmoor. The result? After Arneson ran Gygax and a few friends through a game of Blackmoor, they began a long distance collaboration that resulted in the game known as Dungeons and Dragons, and them forming the company Tactical Studies Rules (TSR) to self publish it. They took ideas and elements from the numerous previous games they had worked on and designed and combined them into the historic roleplaying experience of the game’s first edition.

In the next tabletop article, we’re going to do the first system review of the 1974 first edition of Dungeons and Dragons. This may come as a surprise, but I've never played first edition; I've played every other version through the preceding decades, but never the first. I know all about it of course, but have no experience actually sitting down at a table and playing it. So who knows; maybe we’ll both learn something new.

Until next time.

Last edited: